Flexing Out to Make ABS Parts Delivers on Major Investment

Continental Teves competes with TriFlex flexible manufacturing cells from Turmatic Systems.

Strategically moving into CNC and successfully competing in the intensely competitive ABS brake systems market has meant huge investments in training, meticulous selection of the right technology, and, in the case of Continental Teves (Culpeper, VA), a large dose of self-sufficiency.

Looking at a map of Virginia, it takes a while to find Culpeper, located somewhat strategically 45 minutes south of Washington D.C. It is relatively close to the Appalachian Trail and the Shenandoah National Park and has a nice backdrop of the Appalachian Mountains. All of which are significant (with the possible exception of the mountain backdrop) when you consider that Continental Teves is a subsidiary of Continental AG, a major player in the global anti-lock brake systems (ABS) market.

Though the company is not even sitting on the periphery of "traditional" U.S. automotive manufacturing, the company is "very, very busy." In the words of Patrick Kennedy, engineering manager, and Steve Sautel, production manager, it is "producing millions of ABS valve blocks annually for virtually every North American automaker—whether domestic or transplant." Though they won't address market share issues directly, the two will say that more than 1.4 million parts are run on a bank of eight Triflex U50 flexible manufacturing cells from Turmatic Systems Inc. (St Louis, MO).

Getting to Phase Two

Prior to the Triflexes, Continental Teves produced the valve blocks on a bank of horizontal machining centers arranged in a flexible manufacturing system (FMS) with a common load/unload station and a material handling system tying the arrangement all together. "This was Phase One of our restructuring to modern CNC equipment," Sautel says.

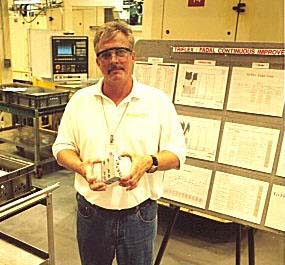

"In Phase Two, we added the TriFlexes. They just proved to be more effective at high volumes and quick changeover." Also taken into the consideration was the critical nature of the ABS valve block. As Kennedy points out, from an engineering/machining point of view, the aluminum part is very complicated. "The block is roughly from 100 mm by 100 mm by 30 mm-to-40 mm wide, so it's relatively small," Kennedy says.

A complex critical product

"However, there are more than 500 critical measured dimensions on each block. Our release criteria for each part call for 1.67 Cpk. Being able to maintain that level says something about dealing with critical dimensions and high volumes concurrently," Kennedy says. Plus, the ABS valve block is a safety-critical component, so each block has to be "fail proof."

Compounding this, Continental Teves makes the same part for about 28 different OEM platforms, and each configuration differs slightly. As a result, says Sautel, there are really 28 different parts that must be regularly changed in and out of the TriFlexes. "Machine accuracy and flexibility have to be very, very high in order to maintain quality and repeatable part integrity. In all honesty, we couldn't do that many part numbers and different configurations if these machines—the TriFlexes—didn't have the combination of flexibility and repeatability to do the job."

As the Culpeper location is a considerable distance from the familiar hubs of automotive manufacturing, there is a need for development of a certain self-sufficiency. Making the switch to CNC equipment, Sautel says, makes a company very quick learners. "You can't rely on people showing up here every time you've got problem, and this applied when we went to horizontal machining centers—and even more so when we turned to TriFlexes."

Two on the learning curve

At the time of its first TriFlex order Continental Teves was ITT Automotive and there was only one other TriFlex in North America. This was the prototype machine at Hastech in Canada. The order was placed through Offenburg, Germany, and the machine arrived in Culpeper around Christmas 1995. So, when the first machine arrived, it wasn't as if Sautel et al could pick up the phone and call Turmatic Systems in St. Louis for advice. In fact, Turmatic Systems and Continental Teves were going through the same learning curve at about the same time on TriFlex technology.

Taking delivery of the first U.S. TriFlex was not like taking delivery of a new machining center. "The only way you get new technology like this to operate to its full potential," Sautel says, "without an in-place complement of support services, installation technicians, part runoffs, debugging and such is to fully immerse yourself in it." That is exactly what Continental Teves did. "We invested heavily upfront in the training process," Sautel says. "We sent groups of people to Germany for periods of three to four months at a time. And that's one part of how you get sophisticated technology like a TriFlex to do what it's designed to do. It's in the training. If you really understand the technology and take the time to be well trained, it will perform just fine."

Flexible workforce needed

A second factor, Kennedy says, in the success (or lack thereof) with this kind of technology is having a flexible workforce...one that's team-oriented and eager to tackle new technology, take ownership, and take the time to become well trained and make it work. "That's what we have here in Culpeper," he says.

Turmatic Systems is a well-informed, well-trained full service and parts organization. We've had technicians here from St. Louis, and if we need a part or component, we get it right away. Today, companies buying TriFlexes don't have to go to Offenburg for assistance or training as we did."

Again, Kennedy and Sautel are saying that critical to the successful operation of any sophisticated equipment or technology is: training, training and more training. And having a flexible, dedicated workforce and a positive workplace atmosphere.

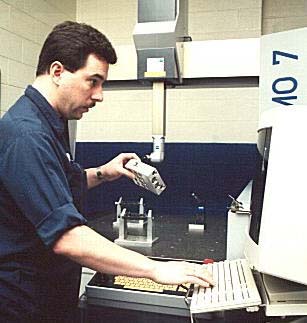

A closer look

Sautel points out that at first glance, a TriFlex might appear awesome in its "perceived complexity"—the tables, the numbers of turrets, spindles and tools, all the simultaneous machining, the multiplicity of machining centers built into a single machine, and so on. However, the way to look at the TriFlex is to think of it as a multi-station rotary transfer line. "If you do that," Sautel says, "it suddenly becomes much easier to deal with, in terms of setup and operation. And it really churns out the parts," Sautel says, "just as a dedicated transfer line would, because in a sense, that's what it is—a small, CNC rotary transfer line.

Unlike a dedicated line, the TriFlex is completely flexible and quick and easy to changeover." Sautel enlarges on the point about the flexibility and quick changeover: "Internally, we've done a lot of work to reduce changeover time. When we ordered the machine," he says," we specified that we'd develop our own processes for changeover. And when the machine arrived from Europe, we modified it to suit our needs."

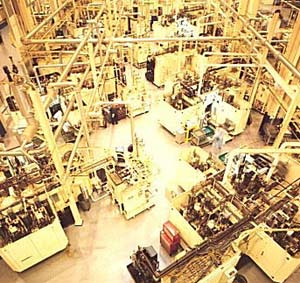

Among the modifications was building special foundations for the 40-ton flexible manufacturing cells—and placing them fairly close together. The idea, Sautel says, was to have a single operator run two machines. However, each TriFlex is designed to come with an elevated platform for the operator to run the machine.

"What we did," Sautel says, "was design foundations so that the TriFlexes sit slightly below ground, to the level of the platforms. This way operators don't have to go up and down platform steps to operate more than one machine. We thought this through before the machines arrived when we were planning the layout for them—not that any special foundation is required for a TriFlex. This is just what we wanted." And the layout is something, again, well-thought out.

The Culpeper facility has some 210 employees and 250,000 sq ft of manufacturing space. However, the eight TriFlexes are in an area of just 5,400 sq ft—tight by anyone's estimation. "This is all by design," Sautel says. "We wanted the TriFlexes in close proximity to each other for ease of operator access and quick changeover capability."

How "quick" is a quick changeover on a TriFlex? About 15 minutes, cut-to-cut, according to Kennedy. "We lose about 15 minutes of parts during a changeover, which is a small handful of parts and is really quite remarkable when you consider how much time is lost changing over most other sophisticated CNC technology. In essence, this is the time required to finish the part in the machine, load the new part program and refill the machine. And we've worked very hard on tooling and part programs to the point that we have the confidence that we can changeover that fast—or faster, depending on the part."

Pushing the envelope

Both Kennedy and Sautel admit that they run the TriFlexes "wide open." They run them as hard as anyone—"perhaps," Sautel says, "harder than anyone else, if only because we really know these machines. The real key to productivity is knowing the technology. In the case of the TriFlexes, we have run them as much as 6 1/2 days a week, 24 hours a day."

Reliability, at Continental Teves, is measured by uptime factored as a percentage of total available running time. According to Sautel, the TriFlexes consistently hit 90% or greater. And as far as breakdowns, maintenance and such, Sautel reports that the Triflexes are "significantly less expensive to run than the other equipment we have."

The other equipment? Sautel points out they still have the FMS they purchased before moving to TriFlexes. Now, however, they've built some redundancy into that system in case one or more of the machining centers should go down. Further, since installation, cycle times on the TriFlexes have fallen by about 20% and plant-wide, overall scrap has declined significantly—which, Sautel points out, undoubtedly has something to do with the TriFlexes, but "may very well have quite a bit to do with the fact that we've just gotten better at machining with CNC equipment and machining this particular part."

Strategy: long term, high end

From a strategic perspective, Sautel and Kennedy will tell you that Continental Teves buys technology for the long term—for the future. When better technology appears on the horizon—even if they have to search the globe to find it and then thoroughly immerse themselves in it, then that's what they'll do. After all, that approach eliminates risk to a great degree, allows Continental Teves to maintain its leadership position, and enables it to add value for its customers.

"There's nothing in our strategic plans that can be called short-term," Sautel says. "We don't believe in buying on price—in purchasing less expensive machines that we'd need to replace every three to five years because they just don't hold up. We've got to have the best, the most flexible, the most reliable."

That is precisely why the strategic decision to move CNC equipment was made in the first place. Sautel says the company knew that CNC was the only answer for reprogramming for second generations of products, or entirely different products. "We've got a very good handle on the refixturing of the TriFlexes—actually, all our CNC equipment—and as long as the part is about the same size, will fit in the machine's envelope, we can re-fixture and reprogram with little effort. This just puts us in a position to respond very quickly to market changes and demands."

One could suggest that buying the first TriFlex in the U.S. was taking a bit of a risk. But both Sautel and Kennedy disagree. "If you do your home work and invest in training," Sautel says, "you not only eliminate significant risk, but you become self-sufficient and significantly agile in your ability to respond."

Turmatic Systems Inc, 11600 Adie Road, St Louis, MO 63043; phone: 314-993-0600