Part 2: Ultra-Precision Machining for "Perfect" Surfaces

By Gavin Chapman, Moore Nanotechnology Systems

As seen in Part 1, the technology contained within the ultra-precision machining system of today is related to its earliest origins and basic forms. The fundamental precision engineering principles continue to be adhered to; yet, at the same time, these time-tested systems are now coupled with leading-edge technologies in controls, drives, and feedback devices.

The need to grind

Single-point diamond turning machines are often provided with add-on grinding attachments to extend their application to those materials that are not diamond machinable. This approach provides an extremely flexible machining system, but extreme care must be taken at the earliest design stage to ensure that the stiffness of the machine is capable of handling the increased grinding forces, and that guarding and coolant containment measures are up to the increased demands. Due to the limited space available, the grinding attachment may also be limited to a single spindle. This might then require wheels to be changed more often than desired for rough grinding and finish grinding operations.

If applications revolve purely around the grinding of mold inserts or for the direct grinding of glass aspherics, then a dedicated grinding machine may be more appropriate. This type of system will be designed to handle the increased forces and coolant volumes and will likely incorporate both a rough- and finish-grinding spindle for improved productivity. The workpiece might also be mounted in a vertical axis orientation that is familiar to many glass-processing operations. The ability to directly grind precision aspheric glass lenses economically has opened a floodgate of applications in both commercial and defense fields.

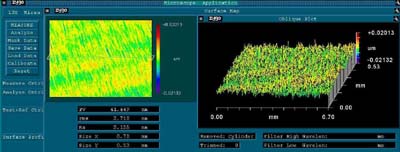

For example, current technology is able to take a 50mm diameter rough glass molding or pre-generated blank and finish-grind to a Lambda/2 figure and 3nm RMS finish, within 15-30 minutes. The specific accuracies and cycle times are, of course, very dependent on specific glass types, such is the process-related nature of grinding.

Machining freeform geometries

A common limitation of the previously mentioned single-point diamond turning and grinding machines is their inherent ability to generate only rotationally symmetrical surfaces. Although these geometries cover the majority of requirements, there is an increasing demand for optics to incorporate more random, freeform geometries. These surfaces might require rastor flycutting or grinding depending on the material.

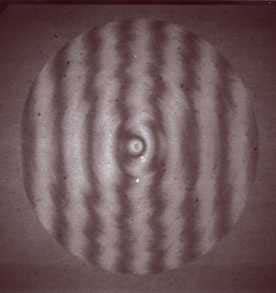

The rastor machining process requires the part to be fixtured in a static condition, while its relationship with the cutting tool or wheel might move simultaneously in 3, 4, or even 5 axes. This type of machining is now possible, either directly by rastor flycutting on nonferrous metals, polymers, and crystals, or by rastor grinding glass or mold inserts. Examples of these "freeform" geometries might be advanced laser printer optics, as shown, or "conformal" windows that blend into the leading edge of an aircraft's wing.

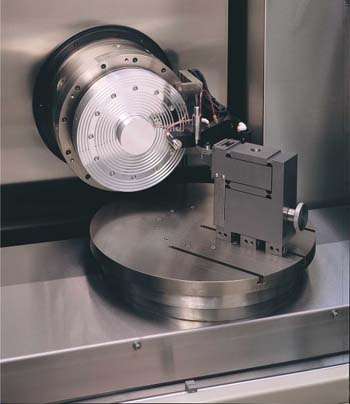

A new breed of multi-axis machines has been developed that is able to generate shapes that are no longer limited to rotational symmetry, but extend to these freeform geometries. This type of machine features three extremely stiff hydrostatic oil-bearing linear axes, X, Z & Y; in addition there are air bearing B & C rotary axes, and an oil-bearing grinding spindle. The machine base comprises a massive natural granite slab, mounted on optimally located air isolation mounts. An advanced CNC controller, with PC frontend, is utilized, while 10nm linear scales provide position feedback.

It is advantageous for a machining system to be able to single-point diamond turn and also grind. This is often accomplished by expanding a lathe platform to one of a grinding platform. This type of machine is, however, often compromised by inadequate guarding, coolant containment, or stiffness. It is therefore critical that the grinding requirements are considered at the point of conceptual design to allow for all the provisions of this demanding process. The illustrations below depict a machine being used in both a single-point diamond turning and grinding mode.

Building advanced features in

Many advanced design features are built into such a machine. An example of this is the integral axis configuration to improve system stiffness, reduce thermal effects, and reduce geometrical errors. The view below demonstrates this technique. Note how the vertical Y axis is buried within the Z axis, rather than stacked one above the other. Also shown is a non-influencing, air bearing counter balance, to allow the vertical axis to be tuned to optimum performance, bi-directionally.

Understanding the relative position of the cutting tool or the grinding wheel on the machine is also critical to the final workpiece accuracy. Automatic systems have been developed for establishing tool/wheel radius, height, and position on the machine relative to spindle centerline. Many of these devices employ kinematic mounting techniques to ensure fast and precise location on the machine, and LVDT or optical probe technology combined with automatic setting software.

Advanced PC-based CNC motion controllers are now used in conjunction with athermalized linear scale feedback devices and state-of-the-art linear motors, allowing surfaces as smooth as 2nm to be generated directly from the machine.

In conclusion

Advances in computer-aided design, and, in particular in Finite Element Analysis, have allowed the mechanical design of machining systems to benefit from specifically selected materials and new structural configurations. This, combined with certain basic rules for oil-bearing slide design, and finely tuned assembly techniques, results in machining systems that are more precise, thermally stable, flexible, more reliable, faster, and less expensive than the machines of yesteryear.

The use of ultra-precision machining techniques, originally developed for commercial applications, then fuelled by demand in defense-related products, is once again being predominantly exploited by commercial industry. Everyday products such as televisions, video players and cameras, contact lenses, binoculars, security systems, compact disc players, personal computers, and many more, rely on advanced manufacturing techniques to produce high performance optics cost effectively. In the future, machine developments will continue to be driven by market requirements. Advances in computing technology and photonics will likely yield further advances in control and feedback technology that will allow ultra-precision machining technologies to continue to advance in line with market requirements.

Moore Nanotechnology Systems LLC, P.O. Box 605, 426a Winchester St, Keene, NH 03431